-

-

23 jan 2021

23 jan 2021Thank you Rotary Club Beirut Cedars!

-

25 nov 2020

25 nov 2020Bassma Communication on Engagement 2020

-

02 sep 2020

02 sep 2020When President Macron meets few NGOs in Lebanon!

-

17 sep 2018

17 sep 2018UNDP Latest Poverty Assessment Report: 30% of Lebanese are Poor

-

09 feb 2018

09 feb 2018الكل في جريدة لنصنع وطنا

-

09 nov 2017

09 nov 2017The world's food import bill is rising despite large production

-

01 nov 2017

01 nov 2017If all societies eventually crumble, could Lebanon be next?

-

21 oct 2017

21 oct 2017Lebanon can't handle refugees anymore: economy minister

-

12 jan 2017

12 jan 2017GivingLoop - New online platform donations by Zoomaal

-

13 nov 2013

13 nov 2013Mills, bakeries agree to maintain price of flour

-

13 nov 2013

13 nov 2013Health Ministry sponsors week of free diabetes testing

-

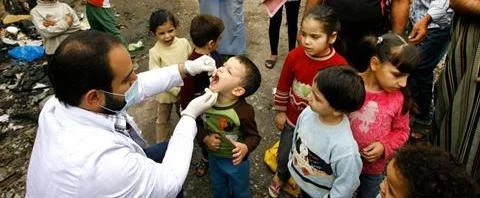

08 nov 2013

08 nov 2013Polio vaccination campaign kicks off in Sidon

-

06 nov 2013

06 nov 2013Lebanon girl celebrates birthday with canned food drive

-

01 nov 2013

01 nov 2013Renovations finally begin on nation’s ‘dangerous’ public schools

-

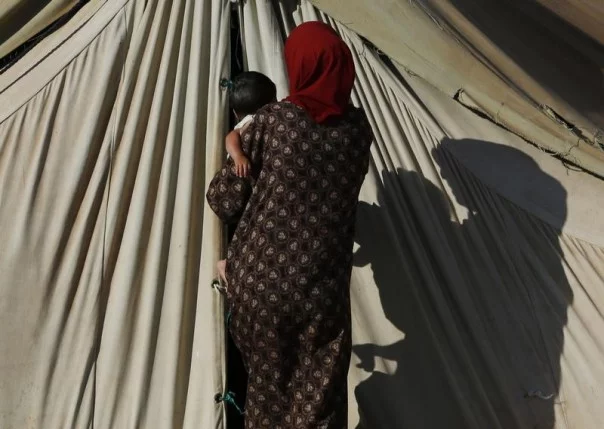

29 oct 2013

29 oct 2013Syrian Refugees Now Equal One-Third of Lebanon’s Population

-

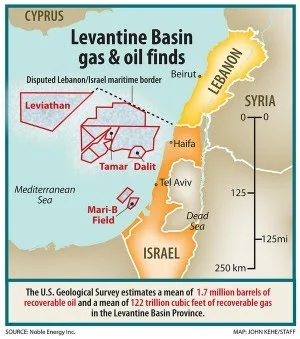

27 oct 2013

27 oct 2013Lebanon says gas, oil reserves may be higher than thought

-

23 oct 2013

23 oct 2013The exodus of Lebanon’s nurses

-

23 oct 2013

23 oct 2013Lebanon gasoline prices slightly up

-

22 oct 2013

22 oct 2013Weighing the scales of justice for drug crimes

-

22 oct 2013

22 oct 2013Hale says U.S. aims to increase Lebanon aid

-

10 oct 2013

10 oct 2013Kuwait''s contributions to Lebanese health sector "unique" - official

-

10 oct 2013

10 oct 2013بهذا المدخول.. تعيش عائلات لبنان

-

09 oct 2013

09 oct 2013Lebanon gasoline prices continue to drop

-

09 oct 2013

09 oct 2013Lebanon’s first outdoor public gym opens in Jbeil’s Wagon Park

-

07 oct 2013

07 oct 2013After shipwreck, Lebanese survivors return to poverty

-

03 oct 2013

03 oct 2013Lebanon students wasting less food

-

21 sep 2013

21 sep 2013Syria war, refugees to cost Lebanon $7.5 billion - World Bank – 19-Sept-2013

-

18 sep 2013

18 sep 2013Lebanon gasoline prices drop after weeks of increases

-

11 sep 2013

11 sep 2013Lebanon gasoline prices rise once more

-

02 sep 2013

02 sep 2013HSBC cuts back in Lebanon, Jordan, Bahrain

-

02 sep 2013

02 sep 2013Demand for anti-anxiety meds still high

-

27 jul 2013

27 jul 2013Courts Suppressing Smoking Ban

-

02 aug 2013

02 aug 2013Study: Hotter temperatures lead to hotter tempers

-

02 aug 2013

02 aug 2013Mers: New virus 'not following Sars' path

-

31 jul 2013

31 jul 2013World Bank Project to Improve Lebanon’s Mobile Internet Services

-

02 aug 2013

02 aug 2013Lebanon's forgotten child laborers

-

24 jul 2013

24 jul 2013Crocodiles Spotted in Beirut River

-

25 jul 2013

25 jul 2013Lebanon's Teacher Layoffs

-

25 jul 2013

25 jul 2013Microfinancing among the poor

-

08 jul 2013

08 jul 2013Addressing social, economic inequalities crucial to achieve sustainability – UN officials

-

25 jul 2013

25 jul 2013Lebanon Affected by Refugee Crises

-

25 jul 2013

25 jul 2013Timing of first solid food tied to child diabetes risk

-

17 jul 2013

17 jul 2013UCC launches petition drive for wage hike

-

25 jul 2013

25 jul 2013Joblessness in the Middle East

-

10 jul 2013

10 jul 2013Does a Child Die Every 10 seconds?

-

10 jul 2013

10 jul 201338 countries meet anti-hunger targets for 2015

-

10 jul 2013

10 jul 2013Ginger Destroys Cancer More Effectively than Death-Linked Cancer Drugs

-

29 jun 2013

29 jun 2013As Doctors Leave Syria, Public Health Crisis Looms

-

03 jul 2013

03 jul 2013Both Residents and Refugees are Struggling in Lebanon

-

06 jun 2013

06 jun 2013Lebanon: Banks central to counter Syrian crisis

-

26 jun 2013

26 jun 2013Lebanese mothers bothered by promotion of formula milk

-

02 jul 2013

02 jul 2013What Lebanon must do to reach its 2015 Millenium Development Goals

-

02 jul 2013

02 jul 2013Beirut: Public Transport Rivals Paralyze Reform

-

02 jul 2013

02 jul 2013Cyprus Crisis Sparks Lebanese Bank Anxiety

-

02 jul 2013

02 jul 2013Beirut Stock Activity Down

-

29 may 2013

29 may 2013Fouad Boutros highway project highly debated

-

02 jul 2013

02 jul 2013WHO: One third of all women face violence

-

28 jun 2013

28 jun 2013Committee to treat drug addiction offers new hope

-

27 jun 2013

27 jun 2013Pledge to improve nutrition signed

-

25 jun 2013

25 jun 2013Lebanon moves to shut down illegal eateries

-

25 jun 2013

25 jun 2013Real estate transactions down more than 8 pct

-

06 jun 2012

06 jun 2012Where does your meat come from?

-

25 jun 2013

25 jun 201316 Hours of electricity promised this summer

-

14 jun 2013

14 jun 2013Like traffic, Jal al-Dib tunnel plans at standstill

-

21 jun 2013

21 jun 2013Gasoline prices continue to rise

-

21 jun 2013

21 jun 2013Public debt reaches $59 billion in April

-

21 jun 2013

21 jun 2013First lady inaugurates women's cardiovascular center

-

21 jun 2013

21 jun 2013Beirut retail sales plunge 14.4 percent in first quarter of 2013

-

21 jun 2013

21 jun 2013Sleiman signs wage hike

-

07 jun 2013

07 jun 2013Achrafieh Residents Save Their Park

-

11 jun 2013

11 jun 2013U.N. launches campaign to combat food waste

-

03 jun 2013

03 jun 2013Most Beirut properties completed in 2012 unsold

-

04 jun 2013

04 jun 2013Stock market activity down 30% to $89m in first four months of 2013

-

10 jun 2013

10 jun 2013Lebanon’s beaches are toxic

-

05 jun 2013

05 jun 2013Gas Prices Go Up at Start of June

-

29 may 2013

29 may 2013Gasoline prices continue slight rise

-

28 sep 2012

28 sep 2012Nearly 30% of gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations among children under five in Lebanon are due to Rotavirus

-

20 may 2013

20 may 2013Power rationing jumps to 9 hours in Beirut

-

21 may 2013

21 may 2013Bank Audi warns over Lebanon’s rapidly increasing public debt

-

22 may 2013

22 may 2013Demand for cheaper cars reflects weaker purchasing power

-

22 may 2013

22 may 2013Lebanon gasoline prices up slightly

-

20 dec 2012

20 dec 2012Are Lebanese children too short?

-

27 sep 2012

27 sep 2012Annual use of mammogram to detect breast cancer is on the rise in Lebanon

-

24 mar 2013

24 mar 2013Approval of public-sector wage increase puts at risk the sustainability of public finances

-

11 apr 2013

11 apr 2013Consumer Confidence in Lebanon drops to Near Record Low in Second Half of 2012

-

23 may 2013

23 may 2013World Bank approves $30m for social protection project

-

21 may 2013

21 may 2013Keeping Kids in School with Meals Program

-

21 may 2013

21 may 2013Gas Prices Remain the Same

-

21 may 2013

21 may 20134G arrives to Lebanon!

-

24 apr 2013

24 apr 2013Lebanon gasoline prices see significant drop

-

26 apr 2013

26 apr 2013Medical organizations announce vaccine campaign

-

19 apr 2013

19 apr 2013Alfa, touch to reduce rates for 3G services

-

23 apr 2013

23 apr 2013Lebanese gas to enter crowded market

-

25 apr 2013

25 apr 201360 Students Hospitalized over Water Contamination in Tripoli

-

11 apr 2013

11 apr 2013The sinister side of Lebanon’s electricity crisis

-

09 apr 2013

09 apr 2013Many Lebanese elderly socially isolated

-

04 feb 2009

04 feb 2009Thank you SOS Chrétiens d'Orient!

-

07 jan 2025

07 jan 2025Thank you SOS Chrétiens d'Orient!

what we do